Aligning Climate Finance Flows with Caribbean Countries’ Climate Resilience Needs

It certainly is a pleasure to gather with stakeholders from various spheres united in our love for the planet and determination to preserve our only living space.

The Caribbean Development Bank (CDB), the Caribbean Community Climate Change Centre (5Cs), and the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States Commission have joined forces to host this event, in order to highlight – yet again – the critical issue of access to adequate, affordable finance for climate action in the region. For us, this is not an academic discussion but literally a matter of life or death for 35 million people in the Caribbean.

Our objective in speaking about “Aligning climate finance flows with Caribbean countries’ climate resilience needs” is to continue to raise awareness about the challenges facing the Region as we tackle the climate crisis while grappling with mounting debt, limited resources to draw on, and low resilience capacity to effectively withstand the impacts of external shocks.

How do we go forward? First, let’s recognise that Caribbean countries understand the urgency of the climate crisis and we have made ambitious commitments to enhance climate resilience while pursuing decarbonisation where and when feasible in nationally determined contributions, National Adaptation Plans, and other key policies and strategies. However, there are several barriers that are inhibiting climate action at a scale that is commensurate with the magnitude of the challenges we face such as: public fiscal constraints including high levels of public debt, difficulties mobilising private sector investment, and difficulties mobilising climate finance. All three factors speak to the uphill task we face marshalling resources for climate action.

Second, I would like to reiterate the call for developed countries to meet the existing USD100 billion per year climate finance commitment which the latest Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development analysis suggests will not likely be met before 2023 or 2024. It is also important that Parties make concerted progress toward a New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) on climate finance. The NCQG must not only set a more ambitious climate finance target but must also address some of the issues that have constrained climate finance flows over the past few years, including: the ad-hoc and unreliable nature of such financial flows; difficulties accessing available climate finance; and insufficient levels of concessionality.

With regard to fiscal and financial constraints, there are two other particularly important points that I must stress:

- there is a pronounced need to adopt more nuanced approaches to assessing when and how concessional financing should be used. We cannot simply assess what level of concessionality is needed to make a particular investment financially viable on paper; instead, we must also assess what level of concessionality is needed to make much-needed capital projects feasible in practice – recognising that many governments, utilities, and other stakeholders in the Caribbean are currently unable and/or unwilling to borrow irrespective of how concessional the rates may be.

- there is a pronounced need to account for climate change vulnerability when determining how to deliver international financial assistance and debt relief. Many Caribbean countries are incurring (and will continue to incur) considerable losses and debt due to their vulnerability to climatic hazards. These same countries are mostly classified as ‘middle-income countries’ and have therefore been unable to benefit from most of the concessional financing and debt relief support provided by the international community, which is mostly earmarked for low-income countries.

Third, as a framework for discussion, I would like to suggest that fundamentally we need to have common understandings, even agreement, on the goals (to what purpose), the specifics of the instruments (e.g., pricing, nature of concessionality), where it should be located and it is marketability, and how the financing will be deployed (implementation). These elements, which hold in general for the broader development agenda, cannot be ignored at the altar of a narrower focus on advocating just for a specific amount of climate funds.

So going forward, it is important that the unique needs of highly vulnerable middle-income countries be taken into consideration when planning and providing such assistance: eligibility for concessional finance could be based on internal resilience capacity (IRC) of countries — their ability to recover and continue to grow (moving us beyond Gross National Income); extent and scope could be based on impact (type and magnitude) of shocks and expected duration to pre-shock metrics; and design of instruments/programs could be based on reforms that could address vulnerability and resilience and thereby shorten the duration for recovery. This pitches assistance toward planned sustainability and resilience and away from temporary or low-resilience firefighting. This was the point I emphasised at COP 26 in Glasgow last year when CDB launched a new vulnerability and resilience measurement framework. Our objective is to have the resilience framework adopted as a global standard and you will hear much more from us on that as we look ahead to COP28.

CDB’s framework includes three tools: the IRC of a country, which estimates the ability to recover from an exogenous shock, the Recovery Duration Adjuster, to anticipate the length of the recovery period after a shock, which is much longer for developing countries when compared with developed countries, and the Vulnerability and Resilience Assessment Tool. These calculations will then provide a more judicious means of determining access to finance for small developing states.

Our approach, which focuses on a holistic approach to sustainable development and underpinned by access to adequate and affordable financing, seeks to integrate the debt sustainability framework of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the investment-growth nexus of the World Bank, and the Resilience Building foundation of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

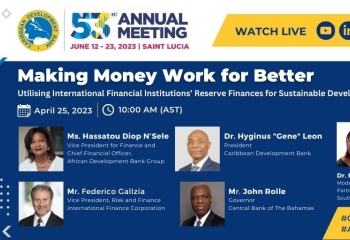

Let me add that it therefore supports fully the compilation and deployment of a Multidimensional Vulnerability Index and is equally aligned with the principles underlying the 2022 Bridgetown Agenda for the Reform of the Global Financial Architecture. In particular, I would like to highlight that we advocate for the deployment of part of the excess Special Drawings Rights of developed countries from the recent (2021) allocation to be used for both the IMF’s Resilience and Sustainability Trust and for channeling through Multilateral Development Banks (e.g., CDB and African Development Bank) for purposes of advancing sustainable and resilient development (e.g, specifically climate adaptation and sustainable energy).

While international financial institutions may have pledged trillions of dollars to finance building resilience against the effects of climate change, those pledges may end up meaning very little if we do not strengthen the “architecture of the international financial system” to ensure that these financial resources efficiently flow to developing countries and assist in meeting their development needs and boosting growth prospects. Some Development Banks which have the potential to expand the flow of climate finance to developing countries face constraints to their lending, especially with respect to their capital adequacy. There are ongoing strategic discussions on the reform of the international financial architecture with respect to solving the long-term lending constraints from capital adequacy. Two possible areas of reform are to reformulate callable capital from being an instrument of last recourse in the event of extreme stress to an instrument with the effect of guarantees that could allow Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) to leverage their capital and expand accessible resources for the urgent financing needs of countries. This can be by means of defining flexible rules for capital calls, making it truly “callable capital”. There is room for developing liquidity insurance mechanisms to allow MDBs access to financing in times of crises, to meet urgent needs of member countries without violating liquidity thresholds. Also, advocacy will be important to crowd-in private sector financing through hybrid and/or non-voting subscriptions in the mezzanine and senior credit funding tranches of MDB balance sheets. All of these would need to be underscored with strength of collaboration among MDBs for advocating unified positions, enhanced synergies with National Development Banks, and developing self-regulatory norms to facilitate better risk assessment by Credit Rating Agencies.

My friends, I am known for speaking frankly and if we are talking about saving the planet, my advice is “a million dollars will not solve a trillion-dollar problem”. Moreso, we will not achieve the balance and equity necessary for a just transition without addressing the issue of access to adequate and affordable finance for nations where the need is greatest. If we call ourselves a global “community” then we are obligated to ensure that the most vulnerable among us are not only able to survive but thrive. I therefore call on our national governments, the international community, and the private sector “let’s give hope a chance”! CDB remains committed to going the last mile, join us!

I thank you.